Diana Lertzman is a woman who is an inspiration to us all. Especially to those of us who have had to struggle with the difficulties of balancing family life and a career in a time where women are becoming more and more invisible in the business world. Diana is proof that you can be a mother, a grandmother, be clever ,sexy and ooze girl power at any time in your life, all it takes is a little determination and confidence.

Diana Lertzman is a woman who is an inspiration to us all. Especially to those of us who have had to struggle with the difficulties of balancing family life and a career in a time where women are becoming more and more invisible in the business world. Diana is proof that you can be a mother, a grandmother, be clever ,sexy and ooze girl power at any time in your life, all it takes is a little determination and confidence.

After her first marriage broke up Diana struggled as a single mum, she put herself through business school and forged a career in finance, she is also a trained cosmetologists.

She is now married to Rick Lertzman who is the co-author of the "Dr. FeelGood" book, and was one of my previous guests here in my Blog . The book is about to be made into a movie where Diana takes on her latest role as executive producer.

So when she agreed to talk with me I was delighted, and this is what Diana had to share with us.

MY INTERVIEW WITH DIANA

Diana, welcome and thank you. I'm really happy you agreed to do this interview. I want to ask you about the early days when you found yourself alone with no career prospects and two small boys to raise.

MY INTERVIEW WITH DIANA

Diana, welcome and thank you. I'm really happy you agreed to do this interview. I want to ask you about the early days when you found yourself alone with no career prospects and two small boys to raise.

Diana: Thank you for talking with me. It was a very frightening time. At that point your world is shaken and you need to find a new order. I took care of my children and tried to get a focus on how I needed to proceed with my life. I finally decided to choose a career path in business. I never went to an employment agency and I found most of the job prospects for women were either as a retail sales clerks, secretarial or cold sales calls. These jobs were pretty much dead end with very little benefits.

The retail chain Victoria's Secret did offer me a benefit - one free bra a month -0 if I worked there. I didn't think that would feed my boys. A car dealership offered a job but said that first I needed to pay $600 to go through their training. Since I neither had the $600 nor was I interested, I passed.

Then fate intervened. I was online in an AOL "thirty-something" chat room when I told my friends there that I was getting up early since I had six interviews the next day. A woman named "Lizzy" suggested I put in an application at where she had worked which was General Electric Finance. She said they offered great benefits. I was aware of the company and was very intrigued. The next day I got up before the crack of dawn, put on a business suit, high heels and a carefully prepared look, dropped my kids at school and went to my six interviews I had arranged. The General Electric interview was my seventh stop that day. I was offered jobs at those first six interviews, but each was a dead end job. I stopped off at G.E. to pick up an application on the way to pick up my boys from school. I was unaware that there had been a purge at G.E. and they needed a new infusion of workers. I was offered a job and to start training the very next day. I agreed to start training at G.E. as the upside was far higher than the other job prospects.

As I began the training, I was overwhelmed at what the company offered. I literally was in tears as I learned about the bonus program, health benefits, pension plan and possible future growth. It was such a godsend at this low point in my life and with two children to raise.

I spent 17 happy years at General Electric and thought I finally needed to explore other opportunities.

How did you meet your husband author Rick Lerztman

We actually met in an online chat room. I had a very sarcastic profile which caught his eye. I wasn't interested in dating anyone from online, but, how should I say this, the prospects were quite slim. I had some disastrous meetings where men seemed to exaggerate about themselves and were quite different when you meet them. Many of them, as I discovered, were living with their mothers in their basement. So I was VERY cautious. Rick had told me he was a physician at a hospital (which he was) but I needled him that he was probably the maintenance man. He was amused and we began a long courtship and became the best of friends.

What was the role of a book publicist like.

It was very stimulating. The lead publicist at the publishing house was not very motivated. I learned in dealing with the media, book store managers, television producers, writers, reviewers and more. I did the legwork necessary to get the book the attention it deserved. I also learned the necessity to use the social media which, unfortunately many of the publishers seem to ignore.

I loved arranging the book signing parties as well. I try to create a stimulating environment where the author can shine.

Are you excited about your new role of executive film producer on the Dr. FeelGood movie, can you explain what the role entails.

I have a certain idea of some of the parameters, but I am sure I will learn much of it on the fly. I'm sure I will end up doing much legwork and "go fer" activities. The responsibilities include many areas including ensuring the crew is assembled, craft services arranged, actors are kept happy, and many of the daily activities needed to be done for the director to be able to do his job. I am very anxious and I am looking forward to the job. I hope that at my age, I can keep up with the energy of those who are younger than I- which is mostly everyone.

After researching the director Philippe Mora I couldn't think of any one better for the job of director for the movie how did the decision to approach Mr Mora come about.

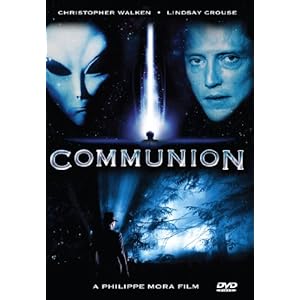

Rick's co- author William J. Birnes has been a longtime friend of Mr. Mora. Bill was a consultant (and appeared in ) his film "Communion" (with Christopher Walken) and had recently appeared in his newest film (soon to be released) "The Sound of Spying".

Bill talked to Phillipe about the Dr. Feelgood book and he was intrigued at the story. He has acquired the rights to the book. Rick and Bill are currently working on the early drafts of the screenplay.

He is a wonderful director and I have greatly enjoyed his films and their originality. I am excited at the prospects of seeing Dr. Feelgood come to life on the big screen. I know he will bring a fresh perspective to the book as he has done with his other films.

You are also a cosmetologist and you own your own store, how's the store going and do you practice anymore?

I stopped practising as a cosmetologist several years ago. The store is doing well and is more of a small boutique. I enjoy the marketing aspect of it. It was challenging putting it together and now that we have got it off the ground, I want to concentrate more on Rick's upcoming book on Mickey Rooney and the film.

Do you have any words of advice to women who maybe just starting a journey similar to your own all those years ago.

The best advice I can give is don't ever ever settle for less than you deserve. Also don't ever let anyone discourage, belittle, humiliate or make you feel like you're less of a person. Always know your worth and what you mean to others - I like to put my family and friends first, - and discover who are your true friends. True friends will help you move - but really TRUE FRIENDS will help you move dead bodies. I also believe that you must make time for yourself.

When I got my divorce, I created a list of items to achieve that I was prevented from doing during first marriage. And always know that enthusiasm is God within.

Diana I think you are a wonderful lady and a great survivor. I wish you the very best of luck please come back and talk to us again. Many thanks.

Fiona, this has been wonderful. I greatly appreciate the time you took to talk with me. The very best to you and your family.

Philippe Mora

Early life and career[edit]

From an early age, the Moras' family life placed Philippe at a focal point of the Australian arts scene. His mother Mirka Mora is a renowned painter, and his father Georges Mora (a French Resistance fighter during WWII) was a leading art entrepreneur and restauranteur. After a brief stint in New York, the family emigrated to Australia in 1951, settling in Melbourne, where the Moras founded the now-legendary Melbourne eateries Mirka Café and Café Balzac. In 1965 they opened the pioneering Tolarno Restaurant and Galleries in St Kilda, which became one of the most influential Australian modern art galleries of the period.The Mora family was closely associated with many of the most prominent artists and writers of the era, including the members of the now-legendary Heide Circle. The family's cafes and their house at Aspendale, south-east of Melbourne, were regularly visited by many of the most prominent figures in the Australian arts and letters, including Charles Blackman, Albert Tucker, John Perceval, Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester, John Olsen, Colin Lanceley, Gareth Sansom, Mike Brown, Martin Sharp, Asher Bilu, Ivan Durrant, Barrett Reid, Brian McArdle, Philip Jones, Barry Humphries, Robert Whitaker, Mark Strizic and Nigel Buesst. The Aspendale house, designed by architect Peter Burns, shared a common courtyard with the neighbouring home of the Moras' friends, influential art patrons Sunday Reed and John Reed, whose son Sweeney Reed became one of Philippe's closest friends.

Mora's first home movie Back Alley, now preserved in the The National Film and Sound Archive, was made in 1964 when he was 15. This was a parody of West Side Story filmed in Flinder's Lane, just behind his mother’s studio at 9 Collins Street. The film features Mora, his brother William and friends, Peter Beilby and Sweeney Reed. His next film, Dreams in a Grey Afternoon (1965) was made as a silent movie but was screened with music by artist Asher Bilu. Shot on 8 mm and blown up to 16 mm, the film features stop-motion animation of sculptures by the Russian-Australian sculptor and painter Danila Vassilieff, and includes rare footage of John and Sunday Reed.

His next project, Man in a Film (1966), was a pastiche of Federico Fellini's 8½ and was also influenced by his recent viewing of The Beatles' A Hard Day's Night. Like its predecessor, it was made as a silent movie, shot on 8 mm and blown up to 16 mm, and again screened with music by Asher Bilu. Man in a Film starred Sweeney Reed and premiered at the Tolarno Galleries in early 1967.

Give It Up (1967), shot in Fitzroy Street, Melbourne, again featured Reed, plus Don Watson and Philippe's younger brother Tiriel. The film symbolised Australian response to the Vietnam War by depicting a woman (played by Zara Bowman) being repeatedly kicked and beaten in the gutter of a busy street while onlookers do nothing.[3]

In 1967, Mora travelled to England and moved into 'The Pheasantry', an historic building in King's Road, Chelsea in London, which housed studios and a nightclub. This residence inspired the name of his production company, Pheasantry Films. A virtual "who's who" of London’s Sixties underground 'glitterati' lived in or close to The Pheasantry, including Martin Sharp, Eric Clapton, Germaine Greer, artist Tim Whidborne, 'prominent London identity' David Litvinoff (production adviser on Nicolas Roeg's Performance), writer Anthony Haden-Guest (author of The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco and the Culture of the Night) and another friend from Melbourne, photographer Robert Whitaker, lensman of choice for many leading rock groups on the scene, including The Beatles and Cream.

As "Von Mora", during this time he contributed cartoons to Oz magazine and assisted co-editor Martin Sharp with the landmark "Magic Theatre" edition. He also made his next short film, Passion Play, shot in the Pheasantry ca. 1967-1968 and featuring Jenny Kee as Mary Magdalene, Michael Ramsden as Jesus, and Mora himself as the Devil.

Mora began painting as soon as he arrived in London, and one of his first London exhibitions was held at the gallery of Clytie Jessop, sister of Hermia Boyd (Hermia Lloyd-Jones), wife of noted ceramic artist David Boyd. Jessop was also a well-known actress and director who played the sinister Miss Jessell in Jack Clayton's classic supernatural thriller The Innocents (1961), and later directed the film Emma's War (1988) starring Lee Remick and a young Miranda Otto.

Jessop invited Mora to exhibit at her gallery in the Kings Road where the show was a great success — much to Mora's surprise - garnering excellent reviews and generating numerous sales. By his own admission, he was so impoverished at the time that he had been forced to use house paint impregnated with insecticide for his paintings, a necessity he turned to his advantage by telling potential buyers that his paintings were "not only art, but they also kill flies".

More exhibitions at Clytie Jessop's gallery followed, with titles such as "Anti-Social Realism" and "Vomart". Eric Clapton bought one of the paintings from the latter exhibition, which depicted a shot-putter about to throw and simultaneously throwing up in a style reminiscent of the provocative Dada art of Barry Humphries.

Mora also held a show at the Sigi Krauss gallery where Martin Sharp also exhibited, featuring pictures painted in black and white. The show also included a grey male rat which he had bought from Harrods. When the rat turned out to be female and gave birth, he tried unsuccessfully to sell the babies as 'multiples' in a limited edition of eight. The rat show attracted the interest of German avant-garde artist Klaus Stacks, who commissioned Mora to produce an edition of a hundred screen prints of the mother rat. In February 1971, Joseph Beuys and Erwin Heerich invited him to sign a "Call to Action" manifesto demanding the freeing of the German art market.

His next show was an Easter Crucifixion exhibition at the Sigi Krauss gallery featuring a life-size sculpture of a sitting man made entirely of meat and offal, similar to Robert Whitaker's controversial "butcher" cover photos for the Beatles' 1966 Yesterday and Today album. At this exhibition Mora also screened his 8 mm 'film painting' Passion Play back-projected onto a screen framed in gold leaf. Although none of the exhibits were by Mora, Stanley Kubrick's art director purchased some of artist Herman Makkink's work for use in the film A Clockwork Orange, notably the giant white phallus and the chorus line of dancing Jesus sculptures.

Mora's provocative and highly symbolic offal exhibit caused a stir. A brick was thrown through the gallery window, which led to it being featured on the cover of Time Out. Later, as the piece began to putrify, the police were called after Princess Margaret, dining at the restaurant across the street, complained about the stench. Detectives from Scotland Yard descended on the gallery and demanded that the sculpture be removed, but gallery owner Krauss refused. The police claimed it was a health hazard and forced him to move it into the garden, where it gradually rotted away.

Trouble in Molopolis (1970), Mora's first feature-length film, was financed by the unlikely partnership of Arthur Boyd and Eric Clapton. It was shot in London, with Mora recalling, "every Australian I knew was pulled into the picture". It was filmed in Robert Hughes' apartment and at the Pheasantry. Germaine Greer played a cabaret singer, Jenny Kee was 'Shanghai Lil', Laurence Hope played a gangster, Martin Sharp featured as a mime and Richard Neville as a PR man. Tony Cahill from The Easybeats created the music with Jamie Boyd before the film premiered at the Paris Pullman cinema in Chelsea, as an Oz benefit. Introduced by George Melly, the star of the film, John Ivor Golding, also made a memorable appearance at the premiere, defecating in the front row and then passing out in an alcoholic coma.

In 1975, Mora wrote and directed, Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?,[1][4] a documentary about the 1930s consisting of a series of film clips and photographs from newsreels, Hollywood films reflecting historical events and those about making movies as well as outtakes, promos, and home movies.[5][6] This was followed in 1976 by his first theatrical release, Mad Dog Morgan,[1] which he also wrote and directed. The film starred Dennis Hopper, Jack Thompson, David Gulpilil, Bill Hunter and Frank Thring.[7][8] Mad Dog Morgan was the first Australian movie to get a 40-cinema release in the United States. It went on to receive the John Ford Award in Cannes in 1976 as part of US Bicentennial celebrations while in 1977 Mora was nominated by the Australian Film Institute for 'Best Director' for the film.

After making The Beast Within, his first film in America, Mora's next project was the parodic superhero musical, The Return of Captain Invincible, starring Alan Arkin, Christopher Lee, Kate Fitzpatrick and an all-star Australian cast, with songs by Rocky Horror Show creator Richard O'Brien. The film has long been regarded as a cult classic and recently became a minor hit in the US when it was re-released on DVD, due in part to its now-poignant final scene, in which Captain Invincible flies past the World Trade Center.

These were followed by A Breed Apart with Rutger Hauer and Kathleen Turner, the werewolf horror movies The Howling II & The Howling III, and the political drama Death of a Soldier, starring James Coburn, which was based on the infamous Melbourne wartime Eddie Leonski murder case.

Mora's next film used the plot of the best-selling book Communion, by his old friend from his London days in the late 1960s, artist, author and broadcaster Whitley Strieber. Released in 1989, the film starred Christopher Walken and was based on Strieber's own alleged encounters with aliens.

Film credits as director as well as occasional writer and actor during the 1990s included the horror spoof Pterodactyl Woman From Beverly Hills (1994) with Beverly D'Angelo, Barry Humphries (in three roles), Moon Unit Zappa and Philippe's children Georges and Madeleine; Art Deco Detective (1994); Precious Find (1996) a sci-fi version of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which reunited two actors from Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, Rutger Hauer and the late Brion James. For television, Mora directed Mercenary II: Thick & Thin (1997), and the films Back in Business (1997), Snide and Prejudice (1998), and Burning Down the House (1998).

In the early 2000s Mora's began work on a still-unfinished film project titled When We Were Modern[9] which in part touched on his own life and experience. The film's plot explores on the tangled relationships of the Heide inner circle — Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester, Albert Tucker and John and Sunday Reed. In the 1940s, after deserting from the army, Nolan took refuge at the Reed's famous house "Heide", and it was here that he made the first paintings in his now world-famous Ned Kelly series. During this time Nolan also conducted an open affair with Sunday Reed, but she refused to leave her husband and marry Nolan, so he subsequently married John’s Reed’s sister, Cynthia Hansen instead. The marriage eventually broke up, and when Cynthia committed suicide in 1976, her death sparked a bitter feud between Nolan and author Patrick White, which lasted until the end of their lives. White excoriated Nolan for abandoning his first wife Elizabeth (who was a close friend of his) and for remarrying (to Mary Perceval) so soon after Cynthia's death.

At the time the project was announced, Mora had cast Australian actor Clayton Watson (The Matrix) to play Nolan, with American actors Alec Baldwin as John Reed and Jennifer Jason Leigh as Sunday Reed. During pre-production, Mora discovered previously unseen home movies of the Heide circle, including the only films of Joy Hester and the Mirka Café. When We Were Modern was to have been dedicated to Sweeney Reed, who committed suicide in March 1979, aged 34. Sweeney was to have featured prominently as a character, and as a tribute to him, Mora reportedly planned to screen some of the footage from Back Alley under the closing credits.

Mora labored on the project for several years but unfortunately - despite the historical significance of the characters it portrayed - it was rejected by Australian film funding bodies. Since that time Mora has worked on several other features and documentaries, but in May 2012 the Deadline Hollywood website reported that he is returning to the film, which he now intends to make as an animated feature, using a combination of hand puppets, stop motion and conventional animation, with the last act in 3D, supervised by 3D cinematographer Dave Gregory. The report also indicates that Clayton Watson will still portray Nolan, but will now perform the role as a voice actor. Interviewed for the report, Mora commented:

"“Personally I loved John and Sunday, and Sweeney Reed, their adopted son, was my best friend as a kid. My parents helped John and Sunday set up the Museum of Modern Art of Australia. This Nolan-Reed ménage is an important story that must be told honestly, no holds barred. It’s a great Australian epic of love and modernism. We are using puppets done in the style of the painters involved.”[10]

Filmography[edit]

- 1969 – Trouble in Molopolis

- 1973 – Swastika

- 1975 – Brother Can You Spare a Dime

- 1976 – Mad Dog Morgan

- 1982 – The Beast Within

- 1983 – The Return of Captain Invincible

- 1984 – A Breed Apart

- 1985 – Howling II: Stirba - Werewolf Bitch

- 1986 – Death of a Soldier

- 1987 – Howling III

- 1989 – Communion

- 1994 – Art Deco Detective

- 1996 – Precious Find

- 1997 – Pterodactyl Woman from Beverly Hills

- 1997 – Snide and Prejudice

- 1997 – Back in Business

- 1998 – Joseph's Gift

- 1999 – According to Occam's Razor

- 1999 – Mercenary II: Thick & Thin

- 2001 – Burning Down the House

- 2009 – The Times They Ain't a Changin'

- 2009 – The Gertrude Stein Mystery or Some Like It Art

- 2011 – German Sons

- 2012 – Continuity

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Thomas, Kevin (11 November 1976). "Mora--The World Is His Scenario". Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California, USA: Eddy Hartenstein). Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Jump up ^ [1]

- Jump up ^ Note that this film is not listed by the Internet Movie Database as of 17 March 2012.

- Jump up ^ "Art: Hard Times". Time Magazine (Time Inc.). 1 September 1975. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Jump up ^ Taylor, Judith; Stricker, Frank (1976). "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? Depression follies of 1976". Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media. pp. 52–53. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Jump up ^ Eder, Richard (8 August 1975). "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? (1975) 'Can You Spare a Dime?' Evokes 1930's". New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Jump up ^ Mora, Philippe (31 January 2010). "The shooting of Mad Dog Morgan". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Jump up ^ "Mad Dog Morgan". Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- Jump up ^ "Director continues to strike a nerve", The Age, 14 May 2002

- Jump up ^ Deadline Hollywood

External links[edit]

|